Using AI to Drive Behaviour Change | Capability @ Lunch Recap

For many of us, large language models (LLM’s) like ChatGPT and Co-Pilot, have become essential to our everyday mahi. While being able to use AI to rewrite your email can feel life changing, this month’s Capability @ Lunch Session focused on using AI to drive real change: behaviour change.

We were joined by Behavioural Scientist, Vishal George, where he reminded us that the quality of what we get from AI depends on the quality of how we ask. When it comes to designing for behaviour change, that means prompting with intention, wisdom, and a healthy dose of critical thinking.

From Designated Drivers to Designed Prompts

Vishal opened the session with a story about designated drivers. The concept, imported to the United States from Scandinavia, didn’t take hold through policy alone. It became the norm because it was deliberately woven into popular culture through partnerships with major Hollywood studios, appearing in movies and TV shows until it became an unquestioned part of going out.

This story was a reminder that behaviour change doesn’t happen by accident, it happens by design.

The kind of interventions that actually shift behaviour are ideas that are thoughtful, evidence-based, and built to stick. But if we want AI to help us generate those kinds of ideas, we need to get better at prompting. The quality of the ideas we get out depends entirely on the quality of the questions we put in.

Talk to AI Like a Human

When Vishal asked the room how many people use ChatGPT or another Large Language Model (LLM) each day, answers ranged from not at all to 50-100 prompts per day, with most people estimating between 10-50 prompts daily.

Vishal emphasised the importance of speaking to AI as though you’re talking to a human. Sure, it might seem odd, but you’re more likely to get a high-quality response if you communicate clearly and use plain language, almost like you’re talking to someone on their first day at work. Vishal noted that as AI use becomes more prevalent, we’re at risk of forgetting how to talk to people. We’re not suggesting you ask your LLM about its weekend, but a ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ here and there to maintain your conversational skills won’t go astray.

The Problem with “Good Enough, Quickly”

Vishal shared a study from Harvard Business Review that compared brainstorming outcomes between entirely human teams and entirely AI-powered teams. The results saw human teams generate more bad ideas, but also more good ideas. The AI teams produced less bad ideas, but also less good ideas, with most outcomes being ‘good enough’ ideas.

The key difference is human teams have conversation: they debate and build on each other’s thinking. AI, on the other hand, gives you “good enough, quickly.” And that’s the trap: when it’s easy to think fast and move fast, we forget to be wise about it.

And let’s be honest: AI is not wise. It’s been trained by a subset of humans, which means it carries all the biases, gaps, and blind spots of its training data. Vishal’s tip? Ask AI what perspectives are missing from its training and make it surface its own limitations.

At the end of the day, we need to take responsibility for AI outputs. If you’re publishing them or using them to inform decisions, you’ve got to own what comes out.

Six Prompts to Work Smarter, Not Faster

Vishal has been developing a set of key prompts to help teams use AI more effectively for behaviour change work. He shared six of them during the session, walking us through a live example. You can access the six prompt cards here, and purchase the full set here.

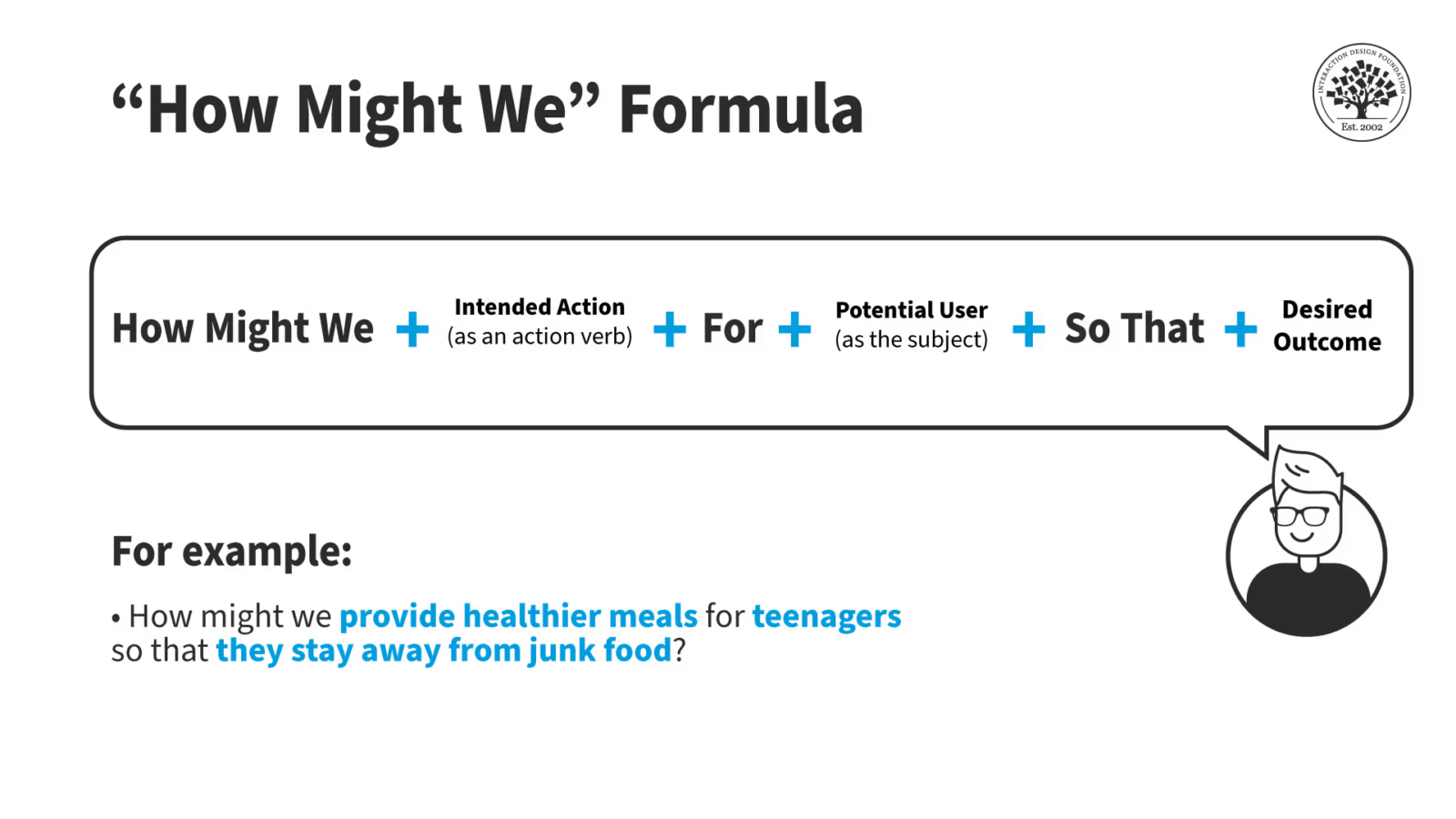

The “How Might We” Formula

He introduced the classic design thinking question format:

“How might we [intended action as a verb] for [potential user/subject] so that [desired outcome]?”

Vishal asked us what behavioural challenges were sitting with us, and the group voted on one to work through together:

“How might we increase voter turnout for Wellington’s local election so that the population is more fairly represented?”

Start with Divergence

Vishal provided three prompts for divergent idea generation:

- Quantity Ideas > Quality Ideas: Generate 20 unique ideas for [problem statement].

- Perspective Play: Generate 15 ideas for [insert context] using:

- Direct Perspective: answer directly.

- Role Perspective: assume you are a PhD-level expert in the domain and answer.

- Third-person Perspective: simulate a long conversation between two people with opposing perspectives, then summarise and answer.

Rate each idea by how confident you are that the answer is useful from 0–100%.

.png/size/w=2000?exp=1761083419&sig=dOkAubZQIgYE7arrxsbHwJQO6kBt8h8hoyYf9Zjd2iU&id=28b1c852-aa30-81f0-ad0a-ddcfb6d51272&table=block)

- Analogical Thinking: Generate 20 surprising ideas for [insert context].

Use analogies from: nature, pioneering thinkers, high-performance sport, collective behaviour, and other complex systems.

For each: name the analogy, explain the relevant principles at play, and apply to this context.

In our example, we opted with option 1: Generate 20 unique ideas for [insert problem statement].

Vishal noted that asking for “unique” ideas encourages the AI to take risks. Higher quantity, but also higher quality. At this stage, you want the robot thinking for you, not with you. You’re going wide. Blue sky thinking. Quantity over quality.

Now, we Converge with Intention

Once you’ve generated a wide range of ideas, it’s time to narrow in. Vishal walked us through the three converging prompts.

.png/size/w=2000?exp=1761083662&sig=bRGdrnYi14wvxGc-38F9rLXB9KIpXTsB13Zg0-Acmew&id=28b1c852-aa30-818f-98c1-f94971f860ed&table=block)

- Effort-Reward Ration: Rate these ideas on:

- A. Effort (1 = very easy to test, 5 = very hard test)

- B. Reward (1 = no learning about context, 5 = major learning about context)

- Then rank ideas from highest reward-per-effort ratio to lowest. Explain the rationale for the top 5 ideas in detail.

.png/size/w=2000?exp=1761083800&sig=a6wVeotXxitRCSu0iCg83BvlbHIQkdBqxNz09oUjPac&id=28b1c852-aa30-8195-b577-eafe380a9bde&table=block)

- What is the scientific consensus?

- Evaluate each idea based on:

– How robust is the supporting scientific research?

– What research suggests this may not work?

– Has it been applied effectively in real-world contexts?

Then rate each idea on a scientific consensus scale (1 star = very weak evidence, 5 star = very strong evidence).

Briefly explain your reasoning and cite all sources. [Insert ideas]

.png/size/w=2000?exp=1761083891&sig=xeDebrhvtwKL0f2ikibrXfHVh9AB7LyVy7dfXZf800Y&id=28b1c852-aa30-8169-bcff-d4615c063cde&table=block)

- Rank these ideas through a human-centred lens. Imagine you are a human‑centered designer ranking ideas. Score each 1–5 for Desirability (how much people want it), Viability (it can be sustainable), and Feasibility (it can be built easily). Because desirability matters most at the early stage, add it twice: Desirability + Desirability + Viability + Feasibility (max score = 20). Rank ideas from highest to lowest and give a detailed explanation for each score. [Insert ideas]

For our voter turnout challenge, we opted for the human-centred lens. Vishal asked the AI to rank ideas based on desirability, viability, and feasibility, noting that we’d upweight desirability since that’s most important at the start of launching an idea. The outcome was a long list of ideas, ready to be fleshed out further.

Watch Out for Hallucinations

Vishal reminded us that AI can and does hallucinate. Don’t take everything it says as fact. If you’re asking for scientific backing, ask it to provide sources. He gave a memorable example: if an LLM only read Garfield comics and you asked what cats like to eat, it might confidently tell you lasagna.

Always verify. Always question. Always own the output.

Save Your Best Prompts

When you find a prompt that works for you, save it. Build a library of effective prompts that you can reuse and refine over time.

And if you’re struggling to figure out a good problem statement or question? Vishal’s advice is simple: talk to the AI the way you’d talk to someone on their first day of work. Use super clear language. When in doubt, ask the model how you should ask it a good question.

Final Reflections

The key takeaway from this session? The prompt is everything. Put your effort into the prompting and planning, not just the output.

AI is a powerful tool for behaviour change work, but only if we use it wisely. That means diverging before we converge, questioning before we accept, and always, always taking responsibility for what we create.

If you want AI to help you design for behaviour change, start by designing better prompts.

What’s Next?

Our next Capability @ Lunch session will explore The Size of the NZ State – Myths and Realities.

These sessions are proudly brought to you by Kāpuhipuhi Wellington Uni-Professional in partnership with Hāpai Public.

Vishal is a behavioural scientist passionate about making behaviour change tools accessible to improve wellbeing across communities. His past work includes projects with EECA, NZ Police, and the Health Quality & Safety Commission, and he previously led behavioural strategy at Ogilvy NZ. With an MSc in Behavioural Economics from the University of Warwick, he also hosts the Wellington Behavioural Science & Economics meetup, fostering collaboration across sectors.

Find more programmes that we offer

Contact usWe customise specific programmes for many New Zealand organisations – from short ‘in-house’ courses for employee groups, to executive education, or creating workshops within your existing programmes or events.